HIRUDO MEDICINALIS

Order RHYNCHOBDELLIDA

Family Hirudidae

Hirudo medicinalis Linnaeus, 1758

Identification

Key, plus text and illustrations, is provided by Elliott and Dobson (2015).

Distribution

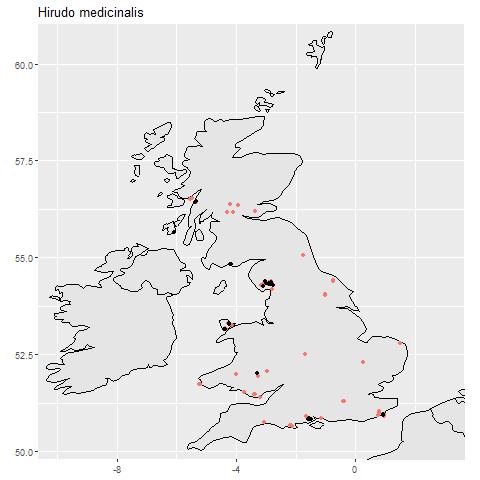

Historically widespread, but now highly localised with populations in Cumbria, Anglesey, the New Forest, Kent, Oban and Islay. Recent records from 15 hectads.

Habitat and ecology

The typical habitat is eutrophic lakes or ponds with dense stands of water plants and hard substrates. Adults feed on the blood of mammals, birds, amphibians and small fish, but the degree of reliance on each host in not known. Their feeding behaviour has long been utilised in medical practice for drawing blood from a patient (phlebotomy or blood-letting). At Romney Marshes, waterbirds and amphibians are the main hosts. The leeches are attracted to disturbances in the water and it is by this means that the hosts are detected. A large mammal such as a cow or deer is unlikely to suffer harm from a leech, but in the case of toads and newts, death has been reported. A leech can take blood up to five times its own weight in a meal which is then digested slowly over several months; thus blood meals need only be very infrequent. Egg cocoons are laid on the shore just above the water line and have been found in July and August. At Lydd, cocoons were laid just below the ground surface among the roots of Hairy willowherb (Epilobium hirsutum) in a band 60-95 cm from the water line. One leech can lay up to seven cocoons, and up to thirty eggs can develop in a cocoon. Hatching takes four to ten weeks depending on temperature. Optimum conditions for activity, growth and breeding include quite high water temperatures, above 19oC (see Elliott and Tullett, 1986). Tadpoles are an important food source for young Medicinal Leeches. Breeding is unlikely to occur before two years of age and the life span is thought to be at least four years.

Red dots are historical (> 10 years old), black dots current (<= 10 years old).

Threats

Historically, the main threat to the Medicinal Leech was over-exploitation of populations to supply the medical trade. British dealers used Medicinal Leeches in thousands in the nineteenth century. A dealer in Norwich kept a stock of about 50,000 leeches. Most were imported from abroad, often packed in damp grass in large sacks, and there was a high mortality rate (Harding, 1910). It has been suggested that the leech trade is partly responsible for the wide distribution of H. medicinalis, since satiated leeches were often released into nearby ponds. However, this trade undoubtedly had a severe impact on the population levels, and several countries introduced export controls at that time. The use of leeches in medicine diminished significantly by the 20th century and since 1981 the species has been fully protected on Schedule 5 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 (as amended).

Other factors have probably contributed to the decline of this species. Many lowland cattle ponds have disappeared in recent decades, either because of the shift to arable agriculture or because cattle troughs and piped water have been supplied to the pastures. In such instances, farm ponds frequently change to marsh or are infilled. Ponds surviving in arable areas are isolated from livestock which previously supported the adult leeches, deer possibly being the only suitable mammalian hosts remaining. Some of the Cumbrian tarns have been deepened to provide cold water conditions suitable for Brown Trout (Salmo trutta), and, in view of the high temperature requirements of the Medicinal Leech for activity, growth and breeding, this lowering of the water temperature probably accounts in part for the decline of the leech in Cumbria (Elliott and Tullett, 1986).

A lack of suitable cocoon laying sites at the water edge may also be a limiting factor. Whilst access to the water by grazing animals is necessary for the Medicinal Leech, excessive trampling and poaching of the banks by livestock can result in silt being released and the loss of cocoon laying sites. In addition, abstraction for irrigation or drinking water may lead to lower water levels which could also result in fewer cocoon laying sites.

The spread of invasive non-native plant species such as New Zealand Pigmy Weed (Crassula helmsii), Water Fern (Azolla filiculoides), or Parrot’s Feather (Myriophyllum aquaticum) which cover the water surface, shading the water, and leading to cooler water temperatures which may slow the development of the leeches.

Increases in the concentration of nutrients, whether from agricultural fertiliser inputs, aerial deposition, or sewage discharges can lead to declines in Medicinal Leech populations. Medicinal Leeches are also affected by pollution from anthelmintic treatments which can enter waterbodies either directly due to livestock defecating in the water or as a result of spreading slurry or manure on adjacent land, or be transferred to the leeches if they feed upon treated livestock.

Finally, the survival of Medicinal Leech populations is dependent on the availability of suitable hosts. They require access to a source of blood either from watering animals or from amphibians. The exclusion of livestock and/or deer from the margins of waterbodies may result in a lack of host animals. Amphibians are important food sources for juvenile Medicinal Leeches, however the risk from Chytrid fungus and other diseases may jeopardise amphibian populations and therefore Medicinal Leech populations.

Management and Conservation

Of the 17 extant populations, 12 of them are located within areas designated as Sites of Special Scientific Interest, however only six of these include the Medicinal Leech as a designated feature: Cors Bodeilio SSSI, Cors Goch SSSI, Kenfig SSSI and Newborough Warrens SSSI in Wales; and Dungeness, Romney Marsh and Rye Bay SSSI, and Jenny Dam SSSI in England.

Neither of the Scottish populations are listed as designated features, nor is the New Forest population, despite these populations being located in SSSIs. It is recommended that Medicinal Leech is therefore added to the list of designated features for Clais Dhearg SSSI and Ardmore, Kildalton and Callumkill Woodlands SSSI in Scotland, and The New Forest in England.

The Freshwater Habitats Trust is leading a conservation project to raise awareness of the conservation needs of the Medicinal Leech and to establish ex-situ ‘ark’ populations for the three largest remaining populations in England. This project builds upon the work of Bristol Zoo which has maintained a population of Medicinal Leech in captivity for nearly 30 years (Spencer and Jones, 2007).

In Scotland, Buglife is leading conservation efforts for the Medicinal Leech as part of the Species on the Edge project. In addition to population monitoring and habitat management works, the project will establish a captive breeding programme with the Royal Zoological Society of Scotland, with a view to undertaking conservation translocations in the future.